A tale of mystery and intrigue from the high seas!

1880—1882

Settlers heading to Canada’s West left their homes in Europe to seek a new life in a new land. These people uprooted their lives and brought to the Canadian prairies their own stories and experiences.

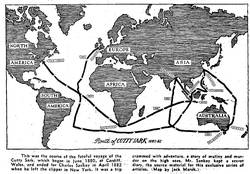

One person’s adventures are particularly worthy of note: Charles Sankey stepped off the deck of the famed tea clipper the Cutty Sark onto North American soil when he was 17 years old. Just as many years passed before he settled in the small town of Waskada in southwest Manitoba. He brought with him the story of his voyage aboard the Cutty Sark, an ill-fated two-year journey filled with unending intrigue and excitement. He kept the details of the journey in a secret diary and told the story to his children.

Murder and Cover-up

The Cutty Sark was a vessel built for speed. The boat had been designed to be a clipper for the tea trade, and, soon after its construction by the Willis and Sons shipping company in 1869, the ship became one of the most widely known vessels on the ocean.

Sixteen-year old Charles Sankey had just returned from his first sea voyage when he was asked to join the crew of the Cutty Sark as senior apprentice. The ship was to begin its journey from Cardiff, Wales, and Sankey arrived on the dock just as the ship was pulling out to sea. The captain was anxious to be out of harbour, so much so that he was leaving on a Friday, which was considered bad luck. Sankey hurried to make it onboard: he hopped on a small boat which took him alongside the ship, then clambered up the hull and over the rail. Little did he know that Fate had given him a boost over the rail that morning, embarking him on the most adventurous and disastrous voyage of his life.

The ship was under the captainship of James Wallace, with first mate Sydney Smith. Smith was a thoroughly unlikable character – a slave driver who allowed no rest on deck. The captain, in contrast was a truly splendid seaman, with a kind word and friendly interest in the apprentices.

Once they reached latitude 40 and the solid westerly winds, the Cutty Sark really showed what she could do, displaying her smart design. They took flight with the wind behind them—all hands on the deck! They worked around the clock to keep the sails in check. Sankey was one of the few Wallace allowed to steer the ship, a matter of great pride to the young man.

The voyage, however, was destined for ill fate. While en route to their destination of Anjer (in Indonesia), discord grew between the first mate, Sydney Smith, and the three negro deckhands on board. One of the hands, Francis, exchanged some blows with the mate after being insulted. Afterward, things appeared to cool down until a few weeks later when the mate got back at Francis by clubbing him over the head. Francis never gained consciousness and died three days later. Afterwards the mood on the ship became very quiet.

Coming into port in Anjer, the crew discovered that Smith was missing and declared that they would not work until the murderer was found. A half-hearted attempt was made by port authorities to locate him, but it was clear that the captain was in on the disappearance. Wallace had made an arrangement with an American ship to take on his first mate.

Soon, orders arrived from Willis directing the Cutty Sark to proceed to Yokohama, Japan. The crew refused, turning mutinous. In order to get control Captain Wallace clapped four of the men in irons.

A scant four days after leaving port, Captain Wallace began to realise the extent of what he had done in helping Smith to escape. He knew there would be an official investigation when they reached Yokohama, and he would very likely be held responsible. The crew, too, was very sullen and angry, calm winds only adding to the frustration aboard the ship. Finally the captain chose between losing his captaincy and claiming responsibility for his misdeeds—he threw himself into the sea! Though the men lowered a boat to search for him, the triangles of shark fins in the frothy water boded evil.

The crew took the captain’s death very closely to heart, believing themselves at fault. The second mate decided to turn back to Anjer and Sankey helped him take sights and navigate the way, sorely missing the captain’s guidance.

Australians on Board

From Anjer, they continued on to Singapore where a new captain came on board. Captain Bruce was a very different sort of man than Captain Wallace had been. At best he was a miserable coward as a sailor, and lacked the nerve to pull the ship through an emergency. He was possessed with the fear of being stranded or running into a cyclone. Many frustrated days were spent when Bruce refused to take advantage of ideal wind and weather. It was a pattern that stayed with the ship for the duration of Captain Bruce’s stint onboard, and the men cursed in private at the humiliation of such a great ship being captained so poorly.

After spending Christmas and New Year’s in Calcutta, the Cutty Sark was decked out with an almost entirely new crew. Only five of the original crew members from London remained, four of whom were apprentices. They secured a cargo of jute, castor oil and tea which was bound for Australia. Upon reaching Sydney several months later, they took on a handful of Australian sailors who—through no fault of their own—caused months of havok aboard the ship. The fact was that these fellows had to be paid very high wages; this caused quite a bit of trouble as they got paid twice as much for doing the same work.

The captain and first mate soon hatched a plan between them. Over a night of drinking, they decided to make the trip so very loathsome that the Australian sailors would choose to take their leave as quickly as possible. With this mission in mind, they very quickly turned the ship into a “hell afloat.”

Cholera Outbreak

The first two Australian deckhands were dispatched by circumstance: while enjoying a rare day of leave in Shanghai, most of the crew contracted Cholera. Only seven of the boat’s number escaped the infection, Sankey included. Those taken ill were sent to hospital where two of the Australians died. Three more crewmen were so badly affected that they took their leave.

The men that did return were a skeletal lot, greatly weakened. Bruce had no sympathy for their condition, and ordered them straight back to work as usual. The crew promptly refused and the captain, thinking he could get rid of the expensive hands by claiming mutiny, took a complaint to the port authorities. But after an investigation and consultation with the doctor, the judge reprimanded the captain, declaring that the men were in no fit state to work. The crew was given two weeks to recover before the ship proceeded.

Mutiny

Due to the delay, their orders were changed – their destination was now New York, and not London as was previously thought. The crew became very sour at this news, as it meant they would be much longer in reaching home. In light of this change of plan, some spirits were obtained to improve the mood. The first mate seized the opportunity to pick a fight with one of the Australian seamen. The captain called the police and deceived authorities into thinking the Australian was at fault. He was sentenced and locked up for two months – another of the expensive hands successfully dispatched!

The crew was very sullen after this, and moved about the ship particularly slowly out of spite for what the captain had done. On their way through the East Indies they stopped in Anjer so the captain could pick up a supply of spirits, as it was again close to Christmas. He and the first mate proceeded to have a glorious drunk. They gave the order late in the day to make sail – a foolish plan, as the tide was coming against them and the winds were all wrong. The crew attempted to follow the captain’s direction, the result of which was very nearly being smashed up on a nearby rock. Things were getting wildly out of control and the crew urged the second mate to take over command.

A full-scale mutiny broke out aboard the ship. The second mate plied the captain with liquor and he soon had to be escorted to his cabin. The crew went through the ship, searching out all of the bottles of liquor and pouring it overboard. They located a safe anchorage about 20 miles away and headed there under fast sail. They anchored and turned in for two days.

The captain eventually wandered up on deck, suspicious as to how his ship had been anchored without him giving the order. As they set sail for New York, the captain began to cut food allowances: first it was sugar, then the lime ration was cut in half – this was more serious from a health perspective, as there were no other fruits or vegetables on board.

The captain questioned Sankey and fellow apprentice Barton about the mutiny and who had been behind it. It was clear that the captain and the mate were getting anxious that a complaint against them would be made after arriving in port.

Starvation on Board

Meanwhile the captain and first mate were not done giving grief to the Australian sailors. Only one was left on board. The first mate took care of him one day while the rigging was being repaired – without warning he let go of the ropes attached to the sail, knocking the Australian overboard. The man was known to be a poor swimmer, and though a search was conducted, he did not resurface. Sankey lost all trust in the first mate after this, no matter how much he insisted it had been an accident.

Even with the Australians out of the way, there was no clear sailing for the Cutty Sark. By the end of February the crew was on half rations, making it clear that the captain had deliberately left the last port with insufficient provisions. The first mate took up a tyrannical watch, keeping the crew always at a run and finding all manner of unnecessary things to be done. The captain continued his questioning, trying to get Sankey and Barton to lay the blame at the feet of the second mate, whom he had begun to suspect. He went so far as to threaten to clap the apprentices in irons if they would not talk, but they remained silent.

The state of provisions on board continued to worsen. A look of hopelessness took over the crew; quiet, patient, and waiting. They became weak, spiritless and indifferent. The outlook was dire when rations were cut from half to a quarter. The crew urged the second mate to take over control again, to put into the port at Bermuda to get supplies. The second mate, however, was not eager to step up to the plate.

Finally they met up with a steamer ship who rescued them from total starvation, transporting two whole boatloads of food to the Cutty Sark. The men fell to with gusto and the ship continued on its way with the first hearty cheer heard onboard in weeks.

Journey’s End

Finally, in April 1882, they docked in New York. This brought an end to Sankey’s journey aboard the Cutty Sark. He took the opportunity of being in North America to take the train up to Toronto where his family had recently emigrated from Ireland. He later learned that the second mate and crew filed charges against the captain – he received a letter from Bruce, asking him to come to New York and appear on his behalf. Sankey wrote the captain and told him at length just exactly what he thought of him at last. The captain and mate had their certificates suspended and the crew members all got bonuses.

While Charles Sankey settled into life in Canada, the Cutty Sark shook itself from the hellish journey and went on to gain fame as a racing clipper under a new and much more accomplished captain. Though designed for the tea trade, she ended up thriving in the wool races, and won undying fame as the fastest sailing ship afloat. Her sea-faring days came to an end in 1954 (after 85 years afloat!) when she was placed in a dry dock in Greenwich. She was opened as a museum in 1957.

. . . . .

Related Articles:

-

The Whole Story, as told by Charles Sankey: "The Cutty Sark."

. . . . .

Author: Teyana Neufeld, 2013.

Sources:

Palmer, Allan. “The Cutty Sark.” (2010-2012). Greenwich Guide. Retrieved 27 Nov 2012. http://www.greenwich-guide.org.uk/cutty.htm

Tillenius, Anna. “Ordeal of the Cutty Sark: A True Story of Murder and Mutiny on the High Seas.” Winnipeg Free Press. May 11-18, 1957.

Images: Winnipeg Free Press. May 11-18. 1957.