In January 14, 1898, the Hartney Star reported that, “Miss E. Pauline Johnson appeared in Lauder last Wednesday with the best entertainment Lauder has ever had. The hall was so full some could not get in.”

This was not an isolated event. That performers of her caliber regularly appeared in small Manitoba towns tells us quite a bit about the times.

When the first settlers found themselves out on our prairies without access to the educational and cultural amenities of European-style “Civilization”, they quickly set about fixing that. Debates and lectures featuring locals were an early favourite, as they required little in the way of staging and could be offered in the schoolhouse or in someone’s living room. Musical evenings were soon popular as well and local talent again was varied and skilled.

Miss Johnson was one of the many notables to visit rural Manitoba. The daughter of a Mohawk chief and an English mother, she was born on the Six Nations Reserve near Brantford Ontario. From her first performance in 1902, she thrilled audiences and challenged them as well with interpretations of her own poetry, with its clear message of native rights, and its condemnation of colonialism. Central to her early performances was, “A Cry From an Indian Wife”, with the lines:

“They but forget we Indians own the land From ocean unto ocean; That they stand Upon a soil that centuries agone Was our sole kingdom and our right alone.”

A gentle reminder indeed! But well presented, and thus well received.

Her performances took her across the continent and to Britain. She came to modest venues, like the hall in Napinka, on the upper floor of a blacksmith shop built in 1899 by Thomas Graham. Tom's daughter Lela remembered talking to Miss Johnson when a blizzard kept everyone away from a recital except her and her father who had to open up the hall. Better than a backstage pass! In Deloraine she played the Opera House. In Melita she entertained the Presbyterian Ladies in 1899 and returned in 1902 and in 1905.

In Boissevain she appeared on several occasions at Wright’s Hall, which often served as a gathering place for stormy political meetings, travelling hypnotists, minstrel shows, local dramatics, and dances.

On one of her visits she was taken to Lake Max where she accepted a gift of the claws from a bear recently shot by John Nelin. She often wore these on a necklace, and although British Columbians insist that the claws came from their province, Boissevain and area residents know better.

By all accounts, the reviews were good, and the appearances were much appreciated.

Now That Is Influence!

When Evelyn Mavis Jones, who grew up in the Tilston, area passed away in 1974 in Vancouver she stipulated that following cremation, her ashes were to be scattered at Pauline Johnson's monument in Stanley Park. She indicated that Miss Johnson had been a favorite poetess and source of comfort to her over the years.

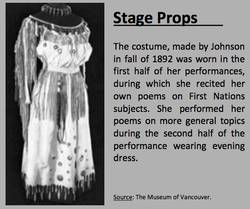

Stage Props:

The costume made by Johnson in fall of 1892. She wore this costume in the first half of her performances, during which she recited her own poems on First Nations subjects. She performed her poems on more general topics during the second half of the performance wearing evening dress.

Source: The Museum of Vancouver.

. . . . .

Author: Ken Storie

Sources:

Boissevain History Book Committee. Beckoning Hills Revisited. “Ours is a Goodly Heritage” Morton – Boissevain 1881 – 1981. Altona. Friesen Printing, 1981 Hartney and District Historical Committee. A Century of Living - Hartney & District 1882 – 1982. Steinbach. Derksen Printers, 1982. Melita - Arthur History Committee. Melita: Our First Century. Altona. Friesen Printers, 1983 Deloraine History Book Committee. Deloraine Scans a Century 1880 - 1980: Altona. Friesen Printers, 1980 Laferriere, Marc. E. Pauline Johnson. The Brant Advocate, August 26, 2013

Wikipedia