The first settlers came into a landscape very different from what we see today. It was dry and it was bare. Trees took root only along stream beds, and the prairie stretched to the horizon unbroken.

The Thomas Richardson family of Dumfries, Scotland went to Pierson by train in 1899.

“ as they made their bumpy way along the prairie road toward Lyleton they had their first real view of the country that was to be their home. There were no trees or bluffs because of the prairie fires that frequently swept through, and one could see for miles around.”

The William Franklin family noted that when they came to the Deloraine area, “there was not a tree to be seen because of prairie fires. Farmers hauled firewood from east of the "fire-break" road from the "Reserve" or from the river near Hartney.”

It was a landscape shaped by the prairie fire, and the fires served their ecological purpose. They allowed for the unbroken expanses of prairie grasses that fed the huge bison herd, that in turn, fed the plains people. Indeed aboriginal peoples dependent upon the buffalo had used fire as a tool for that very purpose.

But to agricultural settlements, they were always a threat. Once underway they were very difficult to stop. In that wide open, environment, when a fire got started, it could go a long way. Even if basic fire fighting equipment and pumps had been available, there was seldom enough water in any given location to even allow for a bucket brigade.

Stories of narrow escapes are found in every local history.

Grace Fulton, from the Lyleton area, reports that:

“A fire once broke out when there were only three children at home, namely, Martha (Mrs. Gregor Campbell), Emma (Mrs. Robert Dandy), and Halden. They set a backfire and saved the stacks only to find

that the sods of the shack were on fire. An old quilt dipped in the creek was used to beat back the fire and save the shack. “

A backfire is a fire started intentionally and forced in the direction of the oncoming flames. They continue to be used in firefighting.

Louise Newcombe recalled in her memoirs: "One fall a prairie fire came very near burning us out. Somehow we managed to fix an old cart with a mule and some harness, and we set out by what was called 'the bush road' a trail which led up over the rim of the hollow, my sister leading the mule, we got safely out of the hollow, making for the Urie farm.”

Mabel (Scott) Barrett, Deloraine area pioneer, offers a glimpse of the hardship that the fires could bring.

“In 1886, a prairie fire swept in and many lost their buildings; with the help of a firebreak and the carpenters, the house was saved, but the sod stable, a horse and a cow that had just been bought that morning, along with some grain, were destroyed. My father was severely burned trying to save a hay stack in the hay meadow.”

Earle Currie remembered; “One day at Fairburn School, the teacher saw a prairie fire rushing from the west toward the school. A side road going north to south on the west side of the school would help hold back the fire. So the teacher started a backfire to burn the grass back to the main fire and saved the school from burning.”

Anne Murray of Lyleton recalled her mother's stories about, "the terror experienced by the early settlers in storms and prairie fires. Often the dry grass of the prairies was set on fire by friction sparks, lightning, or a careless man, and would race across the land at a terrific rate."

Pearl Mason, daughter of Menota pioneer Dan Vail remembered:

We had a stone milk house where milk was strained into pans and put to cool. Mother put the children in the milk house, took a pail of water and broom and went to help fight it.

But the settlers soon learned to deal with the threat, even without a fire department. The boundaries of schoolyards were marked by a wide black, freshly plowed strip which acted as a fire-break. They kept a watchful eye. A cloud of smoke was a signal for everyone to rush to the scene with barrels of water, buckets, and wet sacks to beat out the racing tongues of flame.

In some cases the long arm of the law was sought. In Deloraine it was suggested that the first man who lets a fire get away from him should be prosecuted. In the Montefiore district, in a case before Justice Estlin, a defendant was fined $100 (about $2000 today) for starting a prairie fire.

In the long term, the best defense against the fires was simply to do what the homesteaders came here to do, plow the land, plant some crops and a few trees.

The system of graded grid roads, which replaced the rambling prairie trails, provided a built-in fire-break. Alternating fields of summerfallow also served as an interruption to the progress of a fire. Within a few decades we had changed the landscape to such an extent that the fires were no longer the threat they had been, but as we can see from the reminiscences, they made quite an impression at the time. In the end they were just another challenge to overcome.

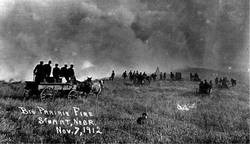

The “Big Fire”

One fire that all the pioneers seemed to remember was the “Big Fire” of 1896.

It started northwest of the Moose Mountains, likely by a spark from a train, and swept into Manitoba. Decades later, old-timers would recall the "year the mountains burned". John McDermit, a boy at the time, recalled that:

“The haze of the fire hung around for days before it reached us at Pierson and it was still there for days after the fire had passed.”

It happened in the early fall when the fields were full of cut and stacked grain. Farmers fought back with fire breaks, but quite a bit of grain was lost.

For a time the town of Pierson was in danger and townspeople back-fired to the railway and saved it, but farther on, the fire jumped the track and went on, carried by the high wind.

There were close calls. The McDermit house was saved by its proximity to a slough. The fire passed right over some sod houses without doing any harm. Mrs. McNea, alone at home, managed to get a rack on to a bare spot - probably one she had burned off - and tied their cows to it, saving them from the fire.

Bertha Forman gives us the story of her mother, Mrs. Alex McNish:

“She got all her tubs placed at the firebreak near the garden. We filled them with water and she had her sacks ready. Hector and I drew more water and kept the tubs filled. Mother fought the fire with the wet sacks. We were so afraid Mother would be burned. However, she managed to save the buildings. Later Charley Elgar got there with his horses and plow and put an extra firebreak around the stacks. I can still remember the smell of the singed hair when he put his outfit through the fire. Father's stacks were saved by his courage.”

. . . . .

Author: Ken Storie

Sources:

Edward History Book Committee. Harvests of Time. Altona. Friesen Printers, 2003. pp 33, Boissevain History Book Committee. Beckoning Hills Revisited. “Ours is a Goodly Heritage” Morton – Boissevain 1881 – 1981. Altona. Friesen Printing, 1981. pp 517, 602 Melita - Arthur History Committee. Melita: Our First Century. Altona. Friesen Printers, 1983. pp 765 Deloraine History Book Committee. Deloraine Scans a Century 1880 - 1980: Altona. Friesen Printers, 1980. pp 663 Davidson, Connie. Gnawing at The Past Lyleton 1869 - 1969. Lyleton Women’s Institute. Leech Printing Ltd., 1969 pp 13, 75

Photos:

University of Saskatchewan Archives https://landingaday.wordpress.com/2010/01/01/newport-nebraska/