Métis interpreters, present during the signing of Canada’s early Numbered Treaties and an integral part of the Boundary Commission Survey, were more than mere translators – they were peacekeepers and diplomats.

1872—1877

Between Two Worlds

Born out of the fur trade, the Métis people grew up between two worlds. Time and time again they found ways to combine their knowledge of European and Aboriginal realities to carve a living for themselves: one example of this was the buffalo hunt. However, there was another niche into which they fell – a political role which bridged the chasm between two widely separate peoples.

Métis were in a unique position on the plains: as descendents of European traders and Native women, they were at once part of both cultures while belonging to neither. They formed a vibrant and distinct culture of their own while maintaining the knowledge and understanding to conduct themselves within either world.

Changing Times Bring an Opportunity

At the end of the 17th Century the North-west was going through intense transition. Aboriginal peoples were growing uneasy with the changes being forces on their traditional lifestyle and the young Dominion of Canada was looking to secure land for their major priority of settlement. One of the two methods by which the government went about doing this was via the Boundary Commission Survey, conducted between 1872 and 1874. The purpose of this survey was to mark the 49th parallel as the Canada-U.S. border between Lake of the Woods and the Rocky Mountains. The second method was treaty making with resident Aboriginal peoples.

Métis were an integral part of both of these endeavours and the role they played was far more complex than simply translating the proceedings. More than just possessing knowledge of Aboriginal languages, the Métis knew the customs and traditions of treaty-making as understood by western First Nations.

More than Guides for the Boundary Commission Survey

The Boundary Commission Survey was the first major governmental presence in western Canada, and there were many opportunities for there to be a misinterpretation of the Commission’s intentions. At the time, the only ceded territory was that which had been negotiated during the signing of Treaties 1 and 2. In lands beyond that there was a tense atmosphere among Aboriginal inhabitants who felt times changing and the resources they had always relied on dwindling.

The Dakota, especially, were worried at the thought of the Commission Surveyors. They had entered Canada from the States, hoping to escape the American Cavalry (see “the Dakota Claim in Canada” ). A local Métis brought a report to Lieutenant Governor Alexander Morris that the Dakota were preparing to stop the Commission Survey due to a concern that it was working in concert with the Americans. In truth, the Dakota were not opposed to the border being defined and their unrest came from the purpose of the survey not being fully or adequately explained to them.

Morris recognised the need to circumvent misunderstanding. The government had a keen interest in acquiring land in the northwest peacefully. They did not have the resources to quell an uprising, and violence would certainly complicate treaty-making and the settlement that was to follow. He suggested that “[Indians] should be advised by men they trust of the real meaning of the boundary surveys.” Thus the Boundary Commissioners employed a troupe of 30 Métis “scouts” who not only knew the lay of the land, but could also travel in advance of the main party and explain its purpose for being there. (The American Survey, in contrast, was accompanied by 70 infantry and 160 cavalry as protection.)

The scouts were dubbed the “49th Rangers,” and led by the respected and celebrated buffalo hunter and trader William Hallett. In addition to being a military escort, their role was to act as guides and hunters, to mark trails and find appropriate campsites. They also brought information to First Nations in the west. They explained the purpose of the survey, distributed gifts as tokens of good intentions, and promised that the government would soon come to make treaties with them. As a result the Commissioners were allowed to pass through unceded territory, not only unharmed, but welcomed as friends and benefactors.

Translators and Mediators During Treaty-Making

After the Boundary Commission Survey, First Nations were eager to make a formal relationship with the new government. They hoped to be informed of the government’s intentions towards their lands and made repeated requests to be treated with. The government moved at its own pace and had a habit of ignoring First Nation concerns until the continued dissatisfaction tumbled towards a threat of violence. Métis such as Pascal Breland were crucial players at this time. Breland travelled between the two parties, explaining one side to the other and keeping violent action at bay. Métis often served to counteract First Nations’ impatience and other negative feelings experienced with the government’s lack of attention.

When treaty negotiations began, Métis such as James McKay served as interpreters and advisors. In particular, Treaty 3 in western Ontario went through a series of negotiations, brought to an end only by the private advice of James McKay and others, in whom the First Nations had confidence and trusted over the treaty commissioners. Métis continued to play an integral part of the first seven of the Numbered Treaties.

Métis understanding of First Nations cultures and their concerns smoothed over many possible misunderstandings and brought explanations accompanied by the correct protocol. Canada’s relatively peaceful expansion west is due in no small part to the diplomatic role played by Métis individuals.

Personalities

Many Métis happened to possess the skills necessary to be a guide, scout, or interpreter simply by a process of osmosis: by growing up between worlds and learning how to cope in both. A handful of Métis embraced this role, a position which was often lucrative and prestigious.

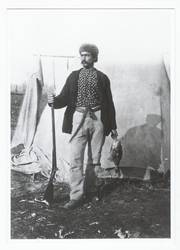

William Hallett

William Hallett was born around 1811 at Fort Vermilion in Alberta to Henry Hallett and the second of his four mixed-blood wives. The family moved to Red River in 1824 where Hallett grew to manhood and became a prominent character in the community. He was highly intelligent, a natural leader of men and an extraordinarily talented buffalo hunter. During the 1860s Hallett was the elected leader of the English-speaking half-breed buffalo hunt out of Red River. The newspaper described him as “universally beloved and esteemed, he has extensive and powerful connections among all classes; of a mild and peaceful disposition himself.” When his father died in 1844, Hallett was freed from having to live up to his father’s expectations and promptly took up independent trading, an occupation outlawed by the HBC.

Hallett was in opposition to Riel during the Red River Resistance and was imprisoned for acting as guide for the would-be lieutenant governor into Manitoba. Riel released him in 1870, but afterwards Hallett suffered from a chronic skin infection (erysipelas) from where the irons in the unheated prison froze his flesh.

After serving the Boundary Commission as Head Scout of the 49th Rangers for one summer, Hallett capitulated to his pain and took his own life with a bullet in the stomach.

James McKay

James McKay was born in 1828 at Fort Edmonton, the eldest child of his French Métis mother and Scottish father. In 1840 the family moved to Red River where McKay became educated. He quickly rose to a position of respect as a politician and wealthy businessman. He developed a fluency in French, English, Cree, Ojibway and Dakota.

Employed by the HBC, he honed his skill as a guide. His marriage to the daughter of Chief Factor John Rowand of Fort Edmonton cemented his position as part of the fur trade elite. He was not a typical Métis of the period: he was educated and wealthy – he owned a thoroughbred stallion. He furthered his position by finding and exploiting a niche where his skills as a cultural mediator were in high demand. He was actively involved in Red River politics: appointed to the Council of Assiniboia in 1868; he served as a member of the Manitoba Legislative Council and as Minister of Agriculture from 1874–1878.

By the 1870s, McKay was a significant figure in the Northwest and his knowledge of the landscape, cultures and people of the Northwest made him a desirable addition to treaty negotiation parties. He interpreted Treaties 1, 2, 3, and 5, in addition to serving as Treaty Commissioner for 6. He died in 1879.

Pascal Breland

Pascal Breland was a French Métis, born in the Saskatchewan River Valley. Later his family moved to the Red River Valley to take up farming. Breland took over the farm after his father died and quickly rose to prosperity as a farmer and trader. His marriage to Marie Grant, daughter of Cuthbert Grant (HBC proclaimed “Warden of the Plains”) furthered his status and prestige. Breland took over Grant’s holdings in St Francois Xavier after he died, and came to be known as one of the wealthiest men in Red River. Breland’s family, like Hallett, opposed Riel and left Red River during the Resistance.

Breland was a key player on the plains before and during the treaty-making process. He was sent by Lieutenant Governor Archibald to learn the wishes of First Nations in the west, and later to appease them when the government was slow to respond.

Not Officially Recognised

These men, among many others, were not officially recognised by Ottawa. In fact, John A. MacDonald insisted that they were not necessary; that only men in the direct employ of the government should be in communication with First Nations. However, it was a regular practice by authorities in the west to depend on men such as Hallett, McKay and Breland, and in many instances it was the only way to connect with distant First Nation communities.

The motives behind the actions of these men are hard to decipher. It could be that they truly believed that the Treaties would help First Nations communities gain access to resources they would need in changing times. The role they filled certainly paid well and utilised specific skills that the Métis took great pride in. Negotiation had been a part of their livelihood for a long time and maintaining good relations was only a further extension of the good relationships they kept in their own dealings with First Nations as partners in the fur trade.

. . . . .

Related Articles:

. . . . .

Author: Teyana Neufeld, 2013.

Sources:

Haag, Larry, and Lawrence J. Barkwell. The Boundary Commission's Metis Scouts: The 49th Rangers. Winnipeg: Louis Riel Institute, 2009.

Goldsborough, Gordon. “Memorable Manitobans: James McKay (1828-1879).” (1 Oct 2012). The Manitoba Historical Society. Retrieved 25 Sep 2012. http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/people/mckay_j.shtml

Stevenson, Allyson. “Men of their own blood: Métis Intermediaries and the Numbered Treaties.” Native Studies Review 18, No.1 (2009): 67-90.

Images: Manitoba Provincial Archives